|

Vincent Pica

Chief of Staff, First District, Southern Region (D1SR)

United States Coast Guard Auxiliary

|

|

May-Day, May-Day, May-Day!! We Are Lost and Sinking!

|

|

Search & Rescue (SAR) is the most recognizable and time-honored task of any mariner, especially the United States Coast Guard. “You have to go out but you don’t have to come back” is a wizened catch-phrase long gone from the guidance offered by senior officers to eager-to-prove-themselves-worthy boat crews. Now, it is risk management, technology and technique. Having saved well over 1,000,000 lives since its founding in 1790, the US Coast Guard can safely claim that they know how to do it. But just what happens in the Command Centers and on the search vessels when a May-Day cry comes in? This column is about that.

Risk Management

USCG Forces know many things about risk management, especially these factors:

1. Every event has some degree of risk;

2. All risks will never be known until presented;

3. Every event requires balancing risk by applying adequate controls and resources, which may be in short supply for the task at hand and;

4. Time is not an ally…

So, the Command Center must get as much as or all of this basic information from the boater in distress and over to the SAR Mission Coordinator (SMC) asap:

1. Just what is the nature of the distress (out of fuel is one thing; sinking or afire is another);

2. What is their last known position;

3. Description of the vessel in distress or, possibly far worse, the person lost overboard;

4. Number of people on board/involved (no one gets left behind by accident);

5. What are the weather/sea conditions at the scene.

This will determine what the SMC specifically tasks the coxswain and crew of the rescue vessel with. The rescue crew will use the time from leaving the dock to arriving at the scene of the event/search area to prep for the task – assigning look-outs, establishing rotations of look-outs to minimize fatigue (which reduces effectiveness), preparing search patterns and associated charting, and, if the vessel or crew is equipped with EPIRBs* and/or PLBs*, coordinate the electronic homing devices on-board with technology at the disposal of the SMC back at the Command Center, such as, most importantly, the Rescue-21 radio/direction-finding system.

|

Rescue-21 – The Modern Day Salvor

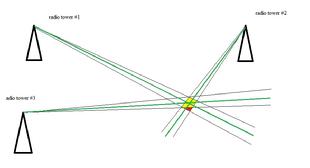

Rescue-21, in addition to being an integral part of the USCG’s 21st century communications system, has a direction finding capability. So, even if the distressed vessel doesn’t have an EPIRB or the crew isn’t wearing PLBs, Rescue-21 can point directly at the source of the radio signal. Although there is a 4o error factor (2o on either side of the direct or rhumb line), multiple radio towers can reduce the search area even further. (see Diagram #1) The green lines indicate the direct or rhumb line from the radio towers to the signal source. With the 2o of error on either side, the red area is eliminated from the search area, thus increasing the odds on the distressed vessel being found.

|

|

| diagram #1 - click to enlarge |

|

|

On Scene

From here, it is very fact-dependent. Is it a person in the water that is the subject of the SAR mission? Is it a missing vessel whose last known position was this point on Earth? In either case, how long ago is it believed that they were here? What “vectors” (wind, current, tides) have been at play since then? What weather/currents/tides are expected from here going forward? How good is all this information? Very good sources narrow the search area. Poor sources expand the search area…

One of the first things that the rescue crew is likely to do is to “drop datum” as they arrive. A radio buoy or other self-locating device (hopefully!) is dropped at the scene so that it can be used to calibrate what actually are the vectors at work here. Another thing that will likely get done as they arrive, as well as during the course of the SAR exercise, is an “aural search” – quiet down everyone and everything possible to listen for a faint call for help. Look-outs are often given look-out posts as far from the engines and radios as possible, to assist in the listening part of the SAR.

The next and most important decision made is what kind of search pattern to run. Sometimes, where the missing person or vessel was lost in a river, the boundaries of the search pattern are well defined. The SMC may even post a vessel at the mouth of the river, just in case the missing person or vessel gets by all the SAR vessels. No one wants them to pass out of the river and out into the open sea…

|

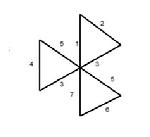

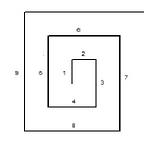

When the search area is large and the last known location is approximate but debris, for example, was found, the search pattern is likely to be a “creeping line” – back and forth across the search area and moving away from the last known position in the direction of the “vectors” – wind/currents/tide. In contrast, when the search area is small (a bay, for example) and the last known position is well known, the search pattern most likely called for is a “vector search” or “Victor Sierra” in SAR-speak. With pie-like patterns, back across the “datum’s” location (see “drop datum” above), the CXN will cut back and forth across that point, looking for the victim or vessel (see diagram 2.) Somewhat between these two conditions, where the search area is small but the last known position is not so well known, the SAR pattern most likely to be used is the “Expanding Square” pattern where the CXN drives in an ever increasing box or square around the last presumed position (see diagram 3.)

|

|

| Diagram 2 - Vector Search (click to enlarge) |

|

|

|

| Diagram 3 - Expanding Square Search (click to enlarge) |

|

|

In any event, the last thing that the SMC wants to hear is this from the crew. “No joy…”

This means that they have done everything that they could and have reached the end of their mission – no joy in finding the missing person or vessel. The SMC can send additional crews out – and likely will until hope becomes the only thing left.

If you are interested in the math about how small your head may appear while bobbing above the waves from a rescue boat at a distance, click here and get the math of "size of an object at a distance." It is a sobering exercise and speaks volumes about the importance of safety of life at sea... suffice it to say this – a human head will appear to be just .03 of an inch in size, when viewed from 600 feet away (our standard track spacing in a search pattern.)

‘*’ Electronic Positioning Indicating Radio Beacon

‘**’ Personal Locator Beacon

|

BTW, if you are interested in being part of USCG Forces, email me at JoinUSCGAux@aol.com or go direct to the D1SR Human Resources department, who are in charge of new members matters, at DSO-HR and we will help you “get in this thing…”

|

| <-- click there to tweet, post or otherwise distribute to the 'net

Have something to add, ask or pass along? Pls do so below! I promise a response.

|

|